Shushing

/I have never—nor will I ever—shush a child. Okay, let me revise that. I’ve probably shushed a baby, which is pretty much my point. Now I’ll be the first to admit that I wasn’t there at the dawn of time, so I can’t say for sure when this business began, but I can say, unequivocally, that from time immemorial, adults have shushed children, teachers have shushed students and stereotyped librarians in horn-rimmed glasses and pencil skirts have shushed all of us.

“Not I,” I shout, trying to keep the big picture in mind: prioritizing relationships and cultivating a Belonging Classroom. Shushing is downright deleterious to those goals.

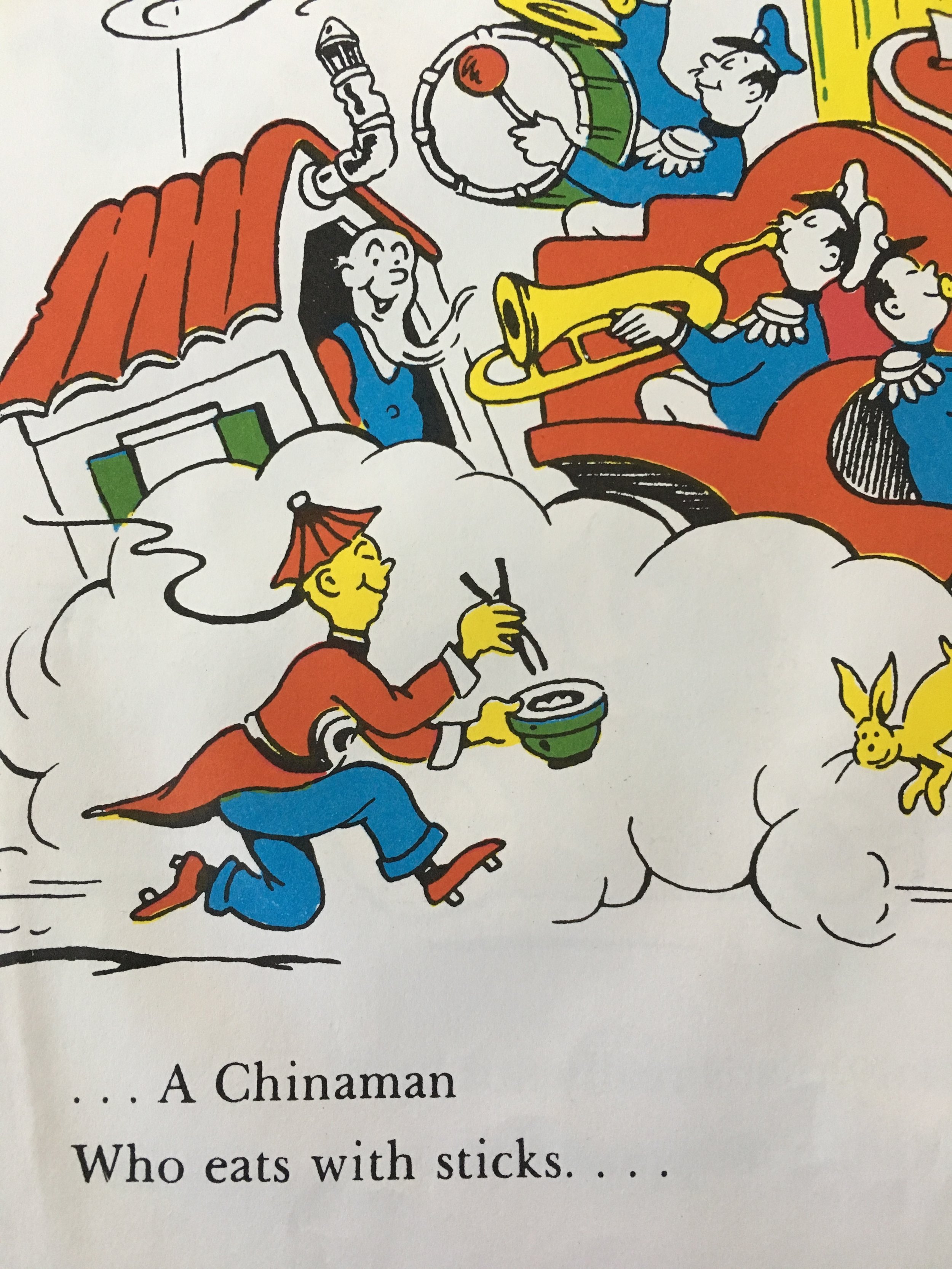

I want my students to talk more. I want them to be brave and take risks and say audacious things. I want them to question me, question each other and question what they have taken at face value. When I do get their attention, what I say must be worth interrupting that flow of ideas. I ask myself, Why do I want their attention? Is there another way to impart this information? If their talking is not about our shared work, then How can I make our work more meaningful and engaging? And when I do need their undivided attention, I get it in a way that reinforces my care and respect for them as well as my own joy in teaching them. Laquisha Hall, Baltimore’s 2018 Teacher of the Year, garnered some delightful strategies.

Aside from reinforcing the message that our students are helpless babies, shushing has another dangerous element. The best classroom relationships are among individuals. When I reprimand my students en masse, I’m creating or cementing an adversarial dynamic, one that, given the emotionally tumultuous state of teenagers, could quickly spark a mob mentality. Then I will be shushing…fellow teachers as I find a good place to hide.

Postscript: When I asked the renowned grammarian Uncle Dennis about the subject/verb agreement in the opening sentence, I confirmed that it was not—nor would it ever be—grammatically correct. After sanctioning my usage in the interest of rhetoric, he queried, “Why are you being so picky with such an idiomatic verb?” Why indeed.